Old Kozana: Village and Family History intertwined

1900

Kozana, a tiny village in the district of Brda on the present Slovenia-Italy border, was the home of both of Daniel's parents, Ivan Maurič and Danila Jakin. In turn almost all of their ancestors for at least the last two hundred years were born, baptised, married and died in this one village.

Brda, part of what is known as the Primorska region, is located on a terrace above the confluence of the Soča and Tolminka rivers and beneath steep mountainous valleys. Situated on a picturesque hill between the villages of Šmartno and Vipolžeand very close to the current border with Italy , Kozana’s population today is less than 400. It is surrounded by numerous vineyards and by cherry and peach orchards. These have long been the drivers of village life and the local economy.

Slovenia's history is complex. Several elements are particularly relevant to the story of Kozana and the families who lived there. They help explain why so many people from this region, including from the Mavrič, Čadež, Reja and Jakin families, looked to a better life abroad.

Traditional Land Ownership

A key to understanding the history of Kozana and the whole Brda district is to understand the history of its land ownership.

From at least the time of Hapsburg dominance of this region in the early 16th century traditional farming practices revolved around serfdom and feudal lords (counts). Bonded labourers struggled under the weight of their obligations to their local count. As well state taxes and tolls grew over time and were payable whether harvests were good or bad. Several peasant rebellions broke out over the 16th and 17th centuries, the last and most famous being the Tolmin Revolt of March 1713 centred on the Brda region.

In 1848 and 1849 the Austro-Hungarian Parliament abolished feudalism, allowing peasants to purchase the land they worked from their lords. But the old land tenancy arrangements survived in Brda region into the 20th century. Before World War One hardly any local farmers owned their own land and many did not until after World War Two. In addition to the holdings of numerous counts the Catholic Church also owned great tracts of land. There were clear class divisions among locals depending on whether they owned their land. At the bottom of the heap were itinerant labourers who did not have even the status of tenant farmers. Even after farmers gained land ownership intermarriages and large families meant holdings quickly became fragmented, making efficient farming very difficult. This was an enduring problem for all Kozana families.

"House" Names

Another incidental outcome of the land holding system was the tradition of "house" names, which came to be used alongside family surnames. Houses were often given a name and over time this house name came to be associated with the family or families that lived in the house. In rural areas this particularly applied to tenant farmers living on land owned by their lords.

At some point the Jakin family lived in a house called Kuraževe and hence this house name became attached to the Jakin family. Another house name used in connection with the Jakin family is Baštjanavi. The house name of the Čadež family is Tinavi. A house name associated with the Mavrič family is Mirkavi.

The existence of both family surname and house names, sometimes used interchangeably in old records can be very confusing for a genealogist trying to track Slovene family history!

Education and Literacy

The first school in the Goriška brda was founded at Kojsko in 1826 and in other places after 1850. Until then, and for many years after, illiteracy was highly prevalent in the area. The population of the Goriška brda area was predominantly rural. In the poorest social strata all family members were required to work for the family just to survive. Many families could not afford to have their children learn reading and writing skills. In the first half of the nineteenth century even wealthy families could only provide education to their first-born sons so they become their successors. A few families of large estate owners and officials in the area also schooled their daughters. Most of these children received their education from private tutors and some girls attended an Ursuline school in Gorica. Only talented pupils pursued further education at Gorica’s normal school. The high social status that literate individuals enjoyed in the community was reflected, among others, in their occupying high positions or the offices of mayor, councillor, church caretaker or in serving as sworn witness to property inventory and witness to last wills and testaments.

As late at 1921, when Ivan Maurič was born, education was still a luxury. He never proceeded beyond primary school, something he was conscious of all his life and an important factor in shaping his views and his determination to better himself.

Early economic immigrants: The Alexandrinke

Driven by their tough economic and political circumstances the people of Brda have a long history of searching. For example, Brda was a major source of emigrant women in the nineteenth century. They came to be known as Alexandrinke from the city of Alexandria in Egypt, where the majority of them worked.

The employment of rural women as wet-nurses and nannies is connected with the long-established European tradition of giving small children away to be fostered by wet-nurses or hiring a wet-nurse for a new-born baby.

Slovenian immigration in Egypt began in the second half of the 19th century. During the building of the Suez Canal and after its inauguration in 1869, the number of rich European businessmen living with their families in Egypt increased. They preferred to employ rural or urban women and girls from Europe for domestic services. It is estimated that round 5,000 mostly young mothers and girls from the Gorica area worked in then-flourishing Alexandria and Cairo, mainly as maids, nannies, cooks and nursemaids.

Slovenian nannies in Egypt with the children of their wealthy European employers, late 19th century

These Slovenian women could earn at least twice as much as they would at home in the economically straitened Gorica area, and spread the good reputation of disciplined, hard-working and well-kempt Slovenian maids far and wide.

The situation in Cairo, 250 km away, was the same. The town chronicles speak clearly about how valued Primorska women were in Egypt, stating that a full 195 bourgeois families were vying for three Slovenian maids, as there simply weren’t any more available. At the same time, their good reputation led to some of them going back to Egypt several times, many of them to stay.

By the first half of the 20th century to the extent that almost every family in villages of Brda had female members at work in Egypt. Men stayed home and were dependent on the money remitted money from their Alexandrinke. Even today in Kozana there are people with Egyptian-born ancestors as a direct result of the Alexandrinke movement.

We do not know whether historically any members of our family were directly affected by this movement but it certainly would have contributed to a migration ethos in the village.

Brda during World War I

World War One had a big impact on all families from the Brda region. Italy, allied with Britain and France, declared war on Austro-Hungary in May 1915. Their 600km border was mostly mountainous, where Austro-Hungarian forces were entrenched. The gentler terrain on either side of the Soča ("Isonzo" in Italian) River – the present-day border between Italy and Slovenia around Brda – was the only practical area for military operations and this is where the Italians decided to launch their attack.

Italian front 1914-1918. Note how the Brda region near Gorizia region was in the centre of the fighting

After Italy entry into the War Brda was occupied almost immediately by the Italian army. Over the next two years some of the bloodiest, but largely inconclusive, battles of the War were fought here. Half of the entire Italian war casualties in the War -- 300,000 men -- occurred on the Isonzo front. On the other side of the conflict Austro-Hungarian losses along this front have been estimated at around 200,000, So between the two sides total casualties exceeded half a million men.

Most of the local villagers from Brda escaped north at the outset of the War. By June 1915 there was serious fighting around the district and Italian occupying forces expelled the remaining villagers to southern Italy. This included both the Reja and Mavrič families (see Reja / Mavrič Families, WW1 and its Aftermath for more details).

Ethnic Cleansing of Slovenes under Fascist Italy provides another incentive to emigrate

The secret Treaty of London in 1915 had promised Primorska (the border areas of modern Slovenia, including Brda) to Italy on the condition Italy joined the Western Allies against the Germany and Austria in "The Great War" (World War 1). After the War, this area was duly transferred to Italy. In the decade that followed the rise of fascism under Mussolini saw Italy adopt increasingly hostile policies towards ethnic Slovenes in this newly incorporated territory. This included forced "Italianisation" of Slovene names and banning the use of the Slovene language in official dealings and education, as well as stripping the Slovene population of other political and cultural rights. In response many Slovenes emigrated without permission from the Italian authorities, who generally were happy to see Slovenes leave the country.

Oilfields of Argentina, where many Slovenes went to work, including Rudolf Jakin and his brothers.

One of the favoured destinations for Slovenes seeking escape from the harsh conditions was Argentina. There have long been cultural ties between Argentina and Italy. Slovenians started to immigrate to Argentina from 1875 onwards in search of prosperity. By the the early 20th century Argentina was one of the richest countries in the world. Already a major agricultural producer Argentina boomed further when oil was discovered in 1918 around Plaza Huincul, in the Province of Neuquén about 1,200 km south west of the capital, Buenos Aires.

Under pressure of the ethnic cleansing at home a second large wave of Slovenian emigrants to Argentina occurred between 1923 and 1929. Peasants from the border regions, including Brda were prominent among this second wave. One such group was three Jakin brothers from Kozana which included Rudolf Jakin, the father of Danila Jakin and grandfather of Daniel Maurice (see Argentina and the Jakins for more details).

Kozana and Brda during World War II

Memorial in Kozana's central square commemorating local villagers massacred by German soldiers in March 1944

Yugoslavia's makeup at the outbreak of World War Two was extremely complex, with two main ethnic groups - the Serbs and the Croats - plus smaller groupings of Albanians, Macedonians and Slovenes. Following German occupation in 1941 and breakup of the country resistance forces soon emerged.

In Slovenia the Germans were supported by a local anti-Partisan force, the "Domobranstvo" (Slovene Home Guard -- in Slovene: Slovensko domobranstvo; German: Slowenische Landeswehr), an anti-Partisan military organization. It was closely linked to Slovene right wing anti-Communist parties and organizations, which provided most of the membership, taking assistance of German between late September 1943 and early May 1945.

The Germans became locked in a protracted and appallingly brutal war against the resistance. The resistance groups were divided into two main movements, Chetniks (Serbian Royalists) and Partisans (Communists).

After the Italian surrender in September 1943 the Germans moved into the Brda region. Due to Brda's history of Italian oppression after its incorporation into Italy at the end of WW1 there wasn't much collaboration with the Germans in this region, unlike some of the areas around Ljubljana where the Domobranstvo was strongest.

Instead Brda was strongly pro-Partisan and its people suffered badly at the hands of the German occupiers as a result. After Italy’s surrender the Partisans captured a lot of Italian weapons and their numbers increased. There is a monument in the centre of Kozana commemorating a massacre of local men in March 1944 in retaliation for an attack on German forces by the partisans.

The linden tree on Kozana’s central square, 1946 not long after the massacre of locals by German soldiers.

The linden tree, 2012

Allied POWs and Slovene Partisans

Thousands of British, Australian and NZ soldiers were captured in North Africa, Greece and Crete and sent to POW camps in Italy and Southern Austria and Maribor.

Two Italian camps were established close to Brda. Many New Zealand and South African soldiers were brought to the region after the Italian capitulation in Sept 1943. Some escaped, fighting with the partisans. Throughout the war there were also Australian escapees from POW camps in Maribor, Graz and elsewhere. They owed their lives to the partisans and civilians who protected and rescued them. In August 1944 100 Australian, New Zealand and British POWs escaped from the Maribor camp in one of the biggest and most successful Allied break-outs during the entire War. They were led by a young Australian army corporal, Ralph Churches. In 2013 the Slovenian Ambassador to Australia presented Ralph with a Slovenian award in recognition of his valour.

Nevertheless there is very little public awareness in Australia of this aspect of our military history. An Australian now living in Kozana, Leigh Thompson, is currently researching and writing an account of this story.

Aftermath of World War II

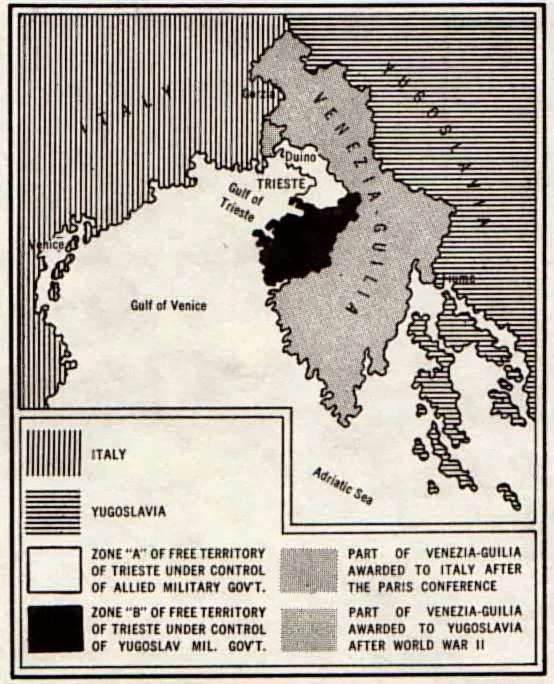

At the end of the War Brda remained under nominal Italian jurisdiction but with US and British army administration. The entire border region encompassing Slovenian Primorska and the Italian cities of Gorizia and Trieste were divided in several zones. The intention was also to cool down territorial claims between Italy and Yugoslavia, due to its strategic importance for trade with Central Europe.

The “Free Territory of Trieste” was established in 1947 as independent territory Adriatic Sea under direct responsibility of the United Nations Security Council. Its administration was divided into two areas: one being the port city of Trieste with a narrow coastal strip to the north west (Zone A); the other, larger (Zone B) was formed by a small portion of the north-western part of the Istrian peninsula.

Zone A of the Free Territory was de facto taken over by Italy and Zone B by Slovenia in 1954. This was formalized much later by the bilateral Treaty of Osimo signed in 1975 and ratified in 1977.

Political and Economic Consequences for Brda of Yugoslav Control

As part of the carve up Brda reverted to Yugoslav administration. Yugoslavia itself fell under communist rule, led by wartime partisan leader Tito. The new government was deeply suspicious of anyone associated with the Chetniks, people thought to be anti-communist and even veterans who had fought alongside the Western Allies during the War. Many of these were murdered, harassed or imprisoned.

Brda region, which until then had been economically tied to Italian Friulia, annexation to Yugoslavia resulted in a number of radical changes. Immediately after WW2 and like the rest of Zone A Brda had been a sort of intermediate region between Italy and Yugoslavia. Because socialism was developing in Yugoslavia, while in Brda support for western-style democracy remained, there were strongly differing political viewpoints in the region regarding the situation in Yugoslavia.

As a result a significant minority, around 10%, of the population decided to move to Italy before the annexation to Yugoslavia and maintain their Italian citizenship. Among them were also some Slovene nationalists who saw the emerging Yugoslav political system as just a form of Stalinism, of which they did not wish to be part. While limited emigration was tolerated, perhaps as a way of getting rid of potential trouble-makers, the political authorities and police in Slovenia made sure that not too many people made the move.

Those that did emigrate left behind farms and houses which progressively fell into disrepair. This was followed by the introduction of the agricultural cooperatives which disrupted traditional farming organisation. Both developments further worsened the economic position of Brda.

The nearby villages of Dobrovo (above) and Šmartno (below) as they were immediately after WW2. These photos, and the further ones also below, are from a collection taken around Brda by the "District National Liberation Committee" during 1946-48 which aimed to prove the Slovene character of the region to bolster the Yugoslav position in the political negotiations then underway to finalise the border with Italy. You can see more photos at http://www.etno-muzej.si/en/digitalne-zbirke/tiskovni-urad . They give some sense of how poor the region was at this time.

Stacking Hay, Kozana, 1946

Working in the kitchen, Kozana, 1945

Pro-Tito procession, Primorska (Brda), 1945

Why did Ivan and Danila leave?

Ivan Maurič certainly held strongly anti-Communist views later in his life. He never spoke of any political activity he was involved in after WW2. But he had served in the British Air Force during the War, possibly creating suspicions about his loyalty and commitment to the new Yugoslav regime. Also for the reasons described above it is clear that living conditions in Kozana by the end of the 1940s would have been poor with little prospect of improvement any time soon.

Against this background his decision to escape from Yugoslavia in 1949 to find a new life far away from post-war Europe, and for his future wife, Danila, to willingly accompany him is not hard to understand. The stories Ivan at War and A New Life as "New Australians" shed further light on this decision which took them both to Australia, changing the course of their lives and of their sons.